Performance is something which should come from the start. If you wait until the end of the flow, you usually end up fighting timing with constraints, placement, and late stage rewrites. Some engineers treat that struggle as normal. I prefer to design for performance up front, then use verification and implementation to confirm that the structure is sound.

In my MicroZed Chronicles posts on leveraging performance and on FIR filter coding for performance, I explored two ideas that keep showing up in real designs. First, higher performance devices and faster clocks can let you trade frequency for area, sometimes enabling different system approaches such as narrower buses clocked faster or time multiplexed techniques like RAM pumping. Second, the same FIR filter specification can produce very different results depending on whether you code a direct form or a transposed form implementation. The filter can be mathematically identical, but the hardware that gets built can behave very differently in terms of critical path and achievable clock speed.

To make that real, I developed a FIR filter solution and used benchmarking to quantify what changed and why. The target was aggressive: a 200 MHz clock with a passband below 25 MHz and a stopband above 30 MHz, implemented on an AMD Artix-7 (xc7a200t-2). FIR filters are ideal for this because they combine delay lines, multipliers, and accumulation, and that is exactly where long combinational paths and carry chains tend to hide.

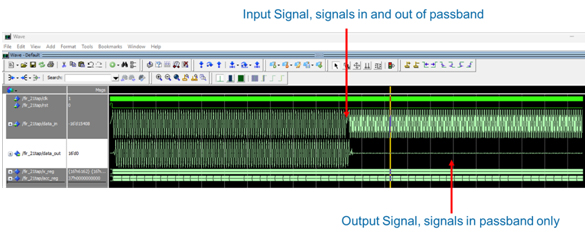

Functionally, everything looked fine in simulation. In band signals passed, out of band signals were rejected, and the waveforms matched expectations.

Filter Functional Simulation

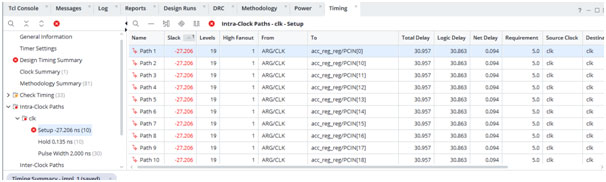

Then the benchmark results from implementation told the truth. The initial build came back with multiple failing paths and a worst negative slack that implied an estimated maximum clock around 31 MHz. That is not a small miss. It is a sign that the RTL structure was fundamentally at odds with the performance requirement.

Vivado Implementation Results – Timing Failed

The cause was the coding structure, not the math. A straightforward direct form approach often creates a large combinational accumulation. When you describe a long chain of adds in one cycle, you are asking the tools to build deep adder logic with long carry propagation. That becomes the critical path. At that point, you can tweak constraints all you like, but you are still trying to push a structure that is not designed for 200 MHz to suddenly behave like it is.

Vivado schematics demonstrating long combinatorial path through DSP Elements

This is where Blue Pearl Visual Verification Suite (VVS) changed the way I approached the problem. Instead of relying on implementation reports alone, I put VVS in the middle of the iteration loop. Take the baseline RTL, run VVS, update RTL based on the findings, then re implement. The benefit is that VVS gives you feedback at the RTL level, where you can still change architecture quickly. It does not just say you missed timing. It highlights the coding patterns that make timing closure difficult, and it does so early enough that you can fix the right thing.

In the benchmarking cycle, VVS made the combinational depth issue obvious, notably through its COMB analysis.

BPS VVS Analysis results.

It reinforced what the timing report was already suggesting, only much faster than having to wait for implementation: the accumulation structure was creating excessive combinational logic. That clarity matters because it points you toward the correct category of fix. Not a cosmetic rewrite. Not a couple of constraints. A redesign of the datapath structure.

The key change was to refactor away from the direct accumulation style and adopt a transposed structure. That aligns with the FIR performance discussion. In a transposed FIR, the sums are naturally expressed in a pipelined way, with registers placed where they break up the critical path, and with a structure that maps cleanly into DSP resources. The result is not just better timing. It is a design where meeting timing is the expected outcome.

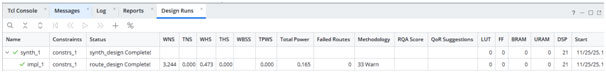

After the refactor, the benchmarking results improved dramatically. The design met the 200 MHz target with margin, and the reported timing suggested a theoretical maximum speed above 500 MHz. The redesign also improved how the resources were used. The earlier implementation showed 304 flip flops plus 21 DSP blocks. The improved version used 21 DSP blocks and removed the extra flip flop count shown in the report summary. That is a strong sign that the refactor was not only faster but also cleaner.

Vivado Implementation Results – Timing Passed

The real win was not just a single pass result. It was how VVS pushed the coding habits that lead to performance. I now treat large combinational math as a red flag by default. I choose architectures that pipeline naturally. I use methodology checks as a design contract so performance issues are caught early, before place and route becomes the main source of feedback.

Better performing code is not just faster code. It is code written so that speed is the default outcome. Blue Pearl Visual Verification Suite helped me get there by making the performance implications of my RTL visible, specific, and fixable.

Adam Taylor